Leben Hi-Fi Stereo Company is a very small company in Amagasaki City, Japan, that hand-builds an exquisite line of vacuum-tube audio electronics. I find it intriguing that Taku Hyodo, founder and main man of Leben, once worked for the comparatively huge Luxman firm. Years back, Luxman went through various corporate owners and spent some time wandering in the desert, before returning to its high-end audio heritage. Whether, as I suspect, Leben was founded during Luxman's years of ownership by car-stereo maker Alpine, or if Hyodo simply wanted to be the captain of his own destiny, I don't know.

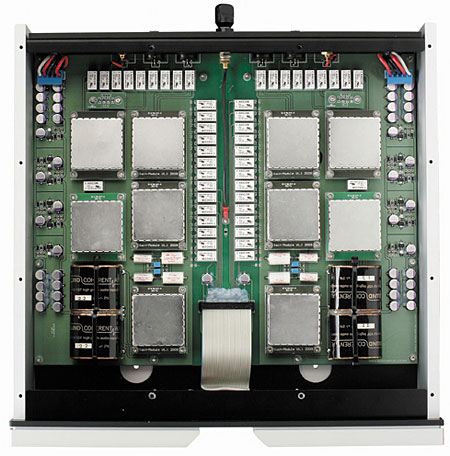

What I do know is that the design and build qualities of the Leben model that I have had the pleasure of borrowing—the CS600, a 32Wpc tubed integrated amplifier ($5895)—are of artisan class. By that I do not mean precious, self-indulgent, or "artistically" flimsy. The 49.5-lb CS600 is built like a brick—if anything, more solid of build and finer of finish than the 1950s and 1960s American hi-fi gear it consciously (though not self-consciously) pays tribute to.

When my friend Bob Saglio stopped by, I showed him the CS600. He took a quick, appreciative look and said, "Some Germans still know how to build things right." I then informed him that Leben was based in Japan. "Some of them, too," Bob allowed. Another audio-savvy visitor was very taken by the sound, but didn't go over to take a close look until after he'd listened quite a bit. When he saw the tubes glowing under the vents in the top panel, he did a double take. "Wow," he said. "This doesn't have the typical 'tube sound.'" But that's getting ahead of the story.

I first encountered Leben Hi-Fi Stereo in the flesh, as it were, at the 2008 Festival Son et Image in Montreal, where exhibitor Coup de Foudre (Thunderclap, en anglais) had a small room set up with the Leben amp driving ProAc Response D Two loudspeakers. My socks were knocked off—not by the power, obviously, or the deep bass, but by the tactility and easefulness of the sound. The music just seemed to have a very easy time of sounding "real." Note that I am not talking about a retro or euphonic sound. There was, instead, a distinct lack of fog on the window between the music and me. It wasn't the biggest window in the lumberyard, to be sure, but it was a very clean one.

When I participated in Stereophile's "Ask the Editors" panel discussion at FSI, moderator John Atkinson asked each of us to mention standout exhibit rooms in a few different categories. If I recall correctly, those categories were Best Cost-No-Object Sound, Best Value for Money, and Personal Favorite. I gave Coup de Foudre's (CdF) Leben-ProAc room my Best Value for Money nod. Not because the CS600 doesn't cost substantial money—it does. Rather, because it and the ProAc speaker struck me as poster products for those who want to buy it once and buy it right.

I can't claim that my advocacy made all that much difference—Stereophile's diligent scribes I'm sure made every effort to visit every exhibit room—but in due course, both Robert Deutsch and John Atkinson visited the CdF room and reported back via Stereophile's FSI blog pages. Robert endorsed the CS600's sound, build, and true value for money. JA later posted: "In some ways—particularly the overall balance and the sheer accessibility of the music—this was the best I heard at the Show despite the system's affordable price."

Take a moment or two to mull over that last little observation—"best I heard"—from John Atkinson, who has measured more than 750 different loudspeakers in the past 21 years. FSI that year featured several ambitious loudspeakers costing over $40,000/pair, and amps all the way up to $90,000/pair. And in terms of "overall balance" and "sheer accessibility of the music," a system anchored by these comparatively modest components served up sound that JA considered best-of-show. Which leads directly to another of my favorite catchphrases: Sometimes it's better to bite off less and chew more thoroughly (the continued relevance of descendants of Quad's ESL-57loudspeaker being more proof of that).

John also mentioned that his first visit to the Leben-ProAc room overlapped with my last—I went back at least twice, to make sure I was hearing what I thought I was hearing: startlingly good sound, especially at the somewhat reasonable prices of $5895 (CS600) and $3500 (ProAc Response D Twos). JA also mentioned on his blog that I had with me a CD-R of tenor Brian Cheney, accompanied by pianist Elaine Rinaldi, singing "Che gelida manina," from Puccini's La bohème, created by Alan Silverman as part of a project in microphone comparison for the New York City audio-engineering community. (JA's photos of that event, where he was one of the listeners, can be foundhere.)

By the way, the Cardas/Soundelux microphones used in that shoot-out ended up being further revised, not only in casework and internals, but also by having undergone a name change. They are now the Bock Audio 5-Zero-7 microphones. (The diaphragm remains George Cardas's Golden Ellipsoid design.) The relevance being not only that my birthday is coming up, but also that both pairs of mikes Cheney sang into were of remarkable resolving power and exceptional dynamic range. Indeed, as I mentioned in my August 2008 report on FSI, as Cheney went for a high C, the CdF person lunged for the volume control and turned it down quite a bit. Despite that protective measure, JA reported that the Leben-ProAc combo transported him back to the recording venue, Sear Sound.